Sidonius’ Epitaph

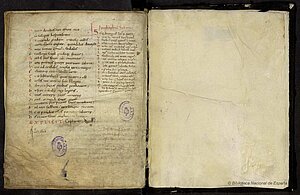

Madrid, National Library, 9448

Written in the interior margin of the last page of codex C (Matritensis 9448, formerly Ee 102, saec. X/XI), as printed by Lütjohann in the introduction to his edition, p. vi, with the corrections of Sirmond.

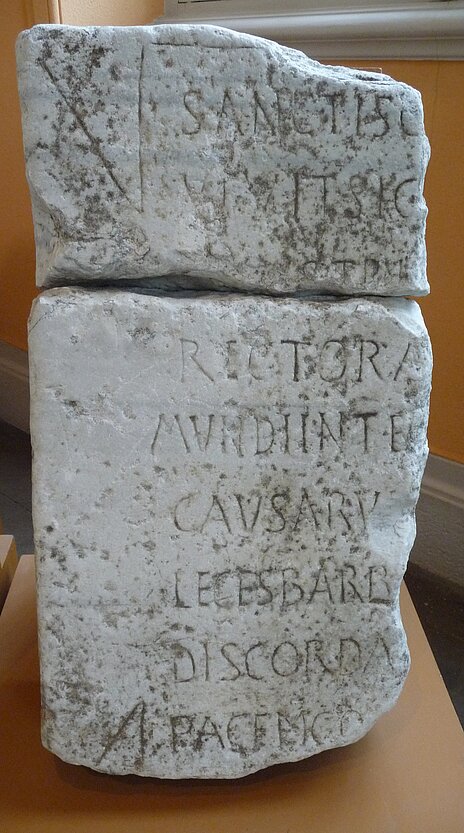

In 1991, fragments of this epitaph (CLE 1516, Le Blant 562, Diehl 1067) were identified in Clermont-Ferrand and could be adduced by Françoise Prévot as proof of the poem’s authenticity. See Prévot 1993a, 1993b (esp. 257-59 = 1999, 77-80) and 1997, and Montzamir 2003 (see also 2014). See also Le Guillou 2002, 280-82, and Benet Salway in Chister Bruun and Jonathan Edmondson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, Oxford, 2015, ch. 18 ‘Late Antiquity’, pp. 364-93, esp. 375.

For the metre (phalaecean hendecasyllables, the same as used by Sidonius in the epitaph of his grandfather, Ep. 3.12.5) and an analysis, see Cugusi 1985, 111-13; another analysis can be found in Mascoli 2004, 166-72. For the date, Stevens 1933: 211-12, and Loyen, xxix. Justus Scaliger, in his Opus de emendatione temporum, bk. 6, p. 614, reckoned the year 480. For the hypothesis that the author was Sidonius’ son, Apollinaris jr, see Condorelli 2013, 279; cf. Furbetta 2015, 250.

| Sanctis contiguus sacroque patri | Close to the saints and to his holy father,¹ |

| vivit sic meritis Apollinaris, | thus lives Apollinaris by his merits; |

| inlustris titulis, potens honore, | noble through his titles, powerful through his office, |

| rector militiae forique iudex, | head of the military, magistrate at the court, |

| mundi inter tumidas quietus undas, | quiet amid the world’s billowing waves, |

| causarum moderans subinde motus | then managing the turmoil of lawsuits, |

| leges barbarico dedit furori; | he imposed laws on the barbarian fury;² |

| discordantibus inter arma regnis | for the realms that were involved in an armed conflict |

| pacem consilio reduxit amplo. | he restored peace by his great prudence. |

| Haec inter tamen et philosophando | Amid all this, however, he also wrote learned works |

| scripsit perpetuis habenda saeclis; | which will be handed down through the ages; |

| et post talia dona Gratiarum | and after these gifts of the Graces, |

| summi pontificis sedens cathedram | sitting in the chair of the supreme pontiff, |

| mundanos suboli refundit actus. | he discharged wordly affairs for posterity.³ |

| Quisque hic dum lacrimis deum rogabis, | Whoever you are, when you come here to implore God with tears, |

| dextrum funde preces super sepulcrum: | extend your prayer over this propitious⁴) grave: |

| nulli incognitus et legendus orbi | may Sidonius, unknown to nobody and to be read by all the world, |

| illic Sidonius tibi invocetur. | be invoked by you there. |

| XII k(a)l(endas) Septembris Zenone imperatore. | August 21, in the reign of Zeno (474-491).⁵ |

1 Probably his predecessor, bishop Eparchius, is meant. Cf. Ov. Ars 3.409-10.

2 Does this suggest that Sidonius partook in compiling the law code of Euric?

3 Or ‘handed over his wordly affairs to his son’?

4 Prof. Matthew McGowan, chair of Classical Studies at the College of Wooster, OH, thinks it possible that dextrum refers to the actual site of the tomb, i.e. to the right of the person reading the inscription (suggestion by e-mail 25.01.07). Köhler 2014, xvi, thinks it points to the tomb of Sidonius’ predecessor Eparchius to the right of Sidonius’ tomb in the chapel of Saturninus in Clermont.

5 AD 479, in the 480s or by 486? (see Cugusi 1985, 111 n. 53). ‘On his sarcophagus, he [Sidonius] made no mention of his bishopric. His offices in the Respublica and his literary activities were what mattered for him. Nor did he date his death by the reign of any local king. Instead, he dated his death by the reign of the eastern emperor, Zeno. Sidonius considered Zeno, as emperor at Constantinople, to be the sole surviving head of the legitimate Roman empire.’ (Brown 2012, 406)

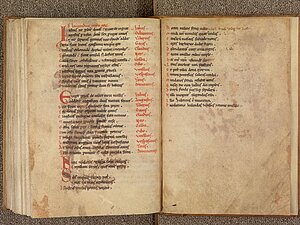

Paris, IRHT, CP 347

Coming as a surprising new development, Luciana Furbetta (2014 and 2015) discovered the epitaph in another manuscript. This privately owned, twelfth-century manuscript (Paris, IRHT, CP 347, formerly in the Schøyen collection) provides a different text of the epitaph, including its date (which had interestingly been conjectured by Mommsen in the preface to Lütjohann’s edition, p. xlix: ‘Quamquam extremum vocabulum non recte se habet scribendumque fuit Zenone Augusto (iterum) consule similiterve’). See also the IRHT website for information about the project in which this manuscript has been studied.

The text in CP 347 runs as follows:

| Sanctis contiguus sacroque patri | . |

| vivit sic meritis Apollinaris, | . |

| inlustris titulis, potens honore, | . |

| rector militiae forique iudex, | . |

| mundi inter tumidas quietus undas, | . |

| causarum moderans subinde motus | . |

| leges barbarico dedit furori; | . |

| discordantibus inter arma regnis | . |

| pacem consilio reduxit amplo. | . |

| Haec inter tamen et facundus ore | . Amid all this, however, he also paid an eloquent tribute |

| libris excoluit vitam parentis | . in his books to the life of his (fore)father/parent |

| et post talia dona Gratiarum | . |

| summi pontificis sedens cathedram | . |

| mundanos suboli refundit actus. | . |

| Quisque hic dum lacrimis deum rogabis, | . |

| dextrum funde preces super sepulcrum: | . |

| nulli incognitus et legendus orbi | . |

| illic Sidonius tibi invocetur. | . |

| Duodecimo Kalendas Septembris Zenone consule. | . August 21, in the consulate of Zeno (i.e. 479) |

Bibliography

Brown, Peter, Through the Eye of a Needle, Princeton, NJ, 2012.

Condorelli, Silvia, ‘Gli epigrammi funerari di Sidonio Apollinare’, in: Marie-France Guipponi-Gineste and Céline Urlacher-Becht (eds), La renaissance de l’épigramme dans la latinité tardive, Paris, 2013, 261-82.

Cugusi, Paolo, Aspetti letterari dei Carmina Latina Epigraphica, Bologna, 1985.

Furbetta, Luciana, ‘Un nuovo manoscritto di Sidonio Apollinare. Una prima ricognizione’, Res Publica Litterarum 37 (2014) 135-57.

—–, ‘L’epitaffio di Sidonio Apollinare in un nuovo testimone manoscritto’, Euphrosyne NS 43 (2015) 243-54.

Köhler, Helga, C. Sollius Apollinaris Sidonius. Briefe, Stuttgart, 2014.

Le Guillou, Jean, Sidoine Apollinaire. L’Auvergne et son temps, Mémoires de la Société ‘La Haute-Auvergne’ 8, Aurillac, 2002.

Loyen, André, Sidoine Apollinaire, vol. 1 Poèmes, CUF, Paris, 1960.

Mascoli, Patrizia, ‘Per una ricostruzione del Fortleben di Sidonio Apollinare’, Invigilata lucernis 26 (2004) 165-83.

Montzamir, Patrice, ‘Nouvel essai de reconstitution matérielle de l’épitaphe de Sidoine Apollinaire (RICG, VIII, 21)’, AnTard 11 (2003) 321-27 ill. plan.

—–, ‘Confirmation de l’existence de l’épitaphe de Sidoine Apollinaire’, in: Bertrand Dousteyssier and Philippe Bet (eds), Éclats arvernes: Fragments archéologiques (Ier-Ve siècle apr. J.-C.), Clermont-Ferrand: Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, 2014, 46-47.

—–, ‘Sidonius’ Presumed Epitaph: Two Manuscripts, Two Fragments of Stone, and Many Questions’, Contributions to the Sidonius Apollinaris Website, 1 July 2023 [available on Contribs and Text page].

Prévot, Françoise, ‘Deux fragments de l’épitaphe de Sidoine Apollinaire découverts à Clermont-Ferrand’, AnTard 1 (1993a) 223-29.

—–, ‘Sidoine Apollinaire et l’Auvergne’, RHEF 79 (1993b) 243-59 (reprinted in Bernadette Fizellier-Sauget (ed.), L’Auvergne de Sidoine Apollinaire à Grégoire de Tours: histoire et archéologie, Clermont-Ferrand, 1999, 63-80).

—–, ‘RICG VIII, 21: Clermont Ferrand, Saint-Saturnin (?)’, no 21 in Recueil des inscriptions chrétiennes de la Gaule antérieures à la Renaissance carolingienne, vol. 8 Aquitaine première, Paris: CNRS, 1997, 116-26.

Stevens, C.E., Sidonius Apollinaris and His Age, Oxford, 1933.

Wood, Ian, ‘The Silence of Sidonius’, in: Alessandro Campus, Anna Chahoud, Gianfrancesco Lusini and Simona Marchesini (eds), Tempus Tacendi. Quando il silenzio comunica, Verona: Alteritas, 2023, 213-28.